By Jeff Foust on 2013 September 7 at 11:24 am ET Friday marked the last day on the job for NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver, who announced a month ago she was leaving the agency to take a job in the private sector. At a reception Thursday evening at NASA Headquarters, she reflected on the four-plus years in that role, NASA Watch reported, from the clashes she had with then-administrator Mike Griffin when she was part of the administration’s transition team after the 2008 election to being perceived as pushing for change at NASA for the sake of change itself. “You can’t choose the time you asked to serve,” she noted in a top-ten list of things she learned during her time in the job. “It was not easy to serve at a time when the shuttle was being shut down and large programs were being cancelled.”

Garver made bigger news, though, in an interview with the Orlando Sentinel, where she said she believed the first launches of the Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket and Orion spacecraft, slated for 2017 and 2021, would likely slip by a year or two each because of insufficient funding. “It’s very clear that we could have slips of a year or two,” she told the Sentinel.

That assessment, she said, comes from experience with past programs like Constellation, which fell behind schedule while being funded at levels similar to SLS and Orion today. A report by NASA’s Office of the Inspector General last month specifically warned of potential delays and cost overruns with Orion, citing the flat funding profile projected for the program versus the more traditional bell-shaped funding profile.

Officials with companies working on the programs disputed that assessment: Boeing’s SLS program manager said she is currently five months ahead of schedule. NASA itself provided a statement to the Sentinel reiterating the party line that the agency’s budget “fully funds” SLS and Orion for a 2017 inaugural launch. Garver didn’t sound convinced. “People are more optimistic than … reality,” she told the Sentinel.

“NASA still has too much on its plate,” she concluded. “We came here trying to avoid that, and I’m afraid we’re headed back in that direction.”

By Jeff Foust on 2013 September 4 at 8:08 am ET Late last week NASA quietly released its final operating plan for fiscal year 2013, with just a month left in the fiscal year. The plan adjusts spending on some agency programs based on the post-sequester cuts to the FY2013 appropriations bill passed by Congress in March. The breakout of spending for agency programs in the operating plan, versus what the administration originally requested for NASA for FY13 back in early 2012, is below (all amounts in millions of dollars):

| Account |

FY13 Request |

FY13 Final |

Difference |

| SCIENCE |

$4,911.2 |

$4,781.6 |

-$129.6 |

| - Earth Science |

$1,784.8 |

$1,659.2 |

-$125.6 |

| - Planetary Science |

$1,192.3 |

$1,271.5 |

$79.2 |

| - Astrophysics |

$659.4 |

$617.0 |

-$42.4 |

| - JWST |

$627.6 |

$627.6 |

$0.0 |

| - Heliophysics |

$647.0 |

$606.3 |

-$40.7 |

| SPACE TECHNOLOGY |

$699.0 |

$614.5 |

-$84.5 |

| AERONAUTICS |

$551.5 |

$529.5 |

-$22.0 |

| EXPLORATION SYSTEMS |

$3,932.8 |

$3,705.5 |

-$227.3 |

| - SLS / Ground Systems |

$1,504.5 |

$1,770.0 |

$265.5 |

| - Orion |

$1,024.9 |

$1,113.8 |

$88.9 |

| - Commercial Spaceflight |

$829.7 |

$525.0 |

-$304.7 |

| - Exploration R&D |

$333.7 |

$296.7 |

-$37.0 |

| SPACE OPERATIONS |

$4,013.2 |

$3,724.9 |

-$288.3 |

| - ISS |

$3,007.6 |

$2,775.9 |

-$231.7 |

| - Space Shuttle |

$70.0 |

$38.8 |

-$31.2 |

| - Space and Flight Support |

$935.6 |

$910.2 |

-$25.4 |

| EDUCATION |

$100.0 |

$116.3 |

$16.3 |

| CROSS AGENCY SUPPORT |

$2,847.5 |

$2,711.0 |

-$136.5 |

| CONSTRUCTION |

$619.2 |

$646.6 |

$27.4 |

| INSPECTOR GENERAL |

$37.0 |

$35.3 |

-$1.7 |

| TOTAL |

$17,711.4 |

$16,865.2 |

-$846.2 |

Every major account suffered a reduction with the exception of education, which saw a slight increase from the $100 million originally requested. Orion and SLS (including ground systems) ended up with somewhat more than what the administration first requested, although less than the pre-sequester levels in the final appropriations bill. Commercial crew, by comparison, got less than requested, but the operating plan funds the program at the same level in that appropriations bill, $525 million, negating the impact of the sequester.

In the sciences, planetary science ended up with nearly $80 million more than requested, although short of the $1.415 billion in the pre-sequester appropriations bill. However, assuming the $75 million set aside in the bill for preparatory work on a proposed Europa mission (not requested by NASA) remains in place, the budget is effectively unchanged from the request. JWST ends up with exactly the amount originally requested to keep that program on track, while other science programs are cut by 6-7 percent from the original request.

By Jeff Foust on 2013 September 4 at 5:46 am ET Comments by former NASA Johnson Space Center director Chris Kraft regarding NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) have attracted some attention this week. “When they actually begin to develop it, the budget is going to go haywire,” he said in an interview with the Houston Chronicle originally published Sunday (getting more attention in an expanded version published in a Chronicle blog post on Tuesday.) “Then there are the operating costs of that beast, which will eat NASA alive if they get there.” Development of the SLS, he concluded, is not “justifiable” for NASA. “It’s not justifiable from a cost point of view, and it’s not justifiable from a mission plan point of view. It just doesn’t make good sense.”

While Kraft’s opinions about SLS are blunt, they’re not new. “The SLS-based strategy is unaffordable, by definition, since the costs of developing, let alone operating, the SLS within a fixed or declining budget has crowded out funding for critical elements needed for any real deep space human exploration program,” he wrote in a Chronicle op-ed in April 2012 co-authored by another former JSC official, Tom Moser. SLS was, in particular, to a threat to JSC, they argued, since building SLS deprived JSC of its “crown jewel” of engineering development and operations work. “SLS is killing JSC. SLS is killing Texas jobs. SLS is killing our national space agenda.”

What’s more newsworthy, perhaps, is his criticism of NASA’s current direction and its management. “[NASA Administrator Charles] Bolden, let’s face it, he doesn’t know what it takes to do a major project. He doesn’t have experience with that,” Kraft said. “He keeps talking about going to Mars in the 2030s, but that’s pure, unadulterated, BS.” He’s also not a fan of NASA’s asteroid initiative, and would rather go back to the Moon. “There’s no reason why you couldn’t set up a factory on the Moon to build solar panels. You could provide enough electrical power on the Moon from solar cells, and eventually you could supply enough power for half the people on Earth with a solar cell farm on the Moon,” he claims (making no mention of the cost or economic payoff of such an initiative.)

Kraft is also not a fan of last year’s “Johnson-style” video, a parody of “Gangnam Style” produced by JSC interns. “I gave ‘em hell,” Kraft said. “I said look, ‘You just spent all of this effort to make a movie, how about spending all of that effort in making a space program go?'”

By Jeff Foust on 2013 August 28 at 7:04 am ET Late August is a quiet period in space policy, with Congress in recess and so many others on vacation, but there are a few items of interest:

Discover magazine published earlier this month an “exit interview” with NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver, who announced plans on August 6 to leave NASA in a month. (The interview was actually conducted prior to that announcement, so it doesn’t cover her plans for leaving.) The interview focuses on NASA’s Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM) plans and the pushback those plans have received from Congress. “I think there are just, right now, some things that because of the partisan nature of this Congress we are not going to be able to convince them,” she said, echoing earlier comments on the issue.

Garver also said that the redirection mission was adopted because of concerns about original plans to send astronauts to a near Earth object. “The long-pull intent was for astronauts to go to an asteroid for some hundreds-of-days mission, but the medical community is not prepared to allow astronauts to do that yet,” she said. In fact, the international exploration roadmap released last week makes virtually no mention of human missions to NEOs beyond NASA’s asteroid redirect mission.

That roadmap, curiously, has attracted a lot of media attention not in the US but instead in Canada. “Canada could be sending its first astronaut to the moon under an ambitious long-term plan being developed by a group of space agencies around the world,” reported the Canadian Press in an article about the report. The Canadian Space Agency is one of the members of the International Space Exploration Coordination Group, which prepared the report, but it did not call out specific roles for the CSA or other agencies in that document. CSA officials said they envision having a Canadian astronaut on the lunar missions envisions for the late 2020s in the report.

That idea has the endorsement of the Toronto Star in an editorial today, saying it would be “a shame if Canada failed to rise to the challenge posed by humanity’s next great leap beyond the surly bonds of Earth.” There’s no mention, though, of the near-term challenges faced by CSA in the form of constrained budgets and an uncertain long-term direction.

Meanwhile, Russian officials are reportedly contemplating an export ban on the RD-180 engine used by the Atlas V rocket. Russia Today, citing a report in Izvestia, said Russia’s Security Council was considering blocking the export of the engines, for reasons not explicitly clear in the article but possibly linked to the Atlas V’s use in launching military payloads. Any ban would not take effect until 2015, according to the report, but would still leave United Launch Alliance with few options to deal with the ban. A Russian space policy expert called the proposed ban “stupid” since it would deprive engine manufacturer NPO Energomash of its main business. Stupidity, though, is not necessarily a primarily criterion in policy decisions.

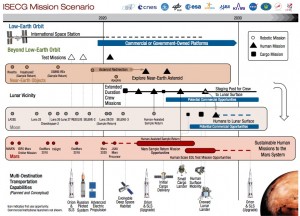

By Jeff Foust on 2013 August 21 at 7:21 am ET  The ISECG roadmap of missions to asteroids, the Moon, and Mars. (Click to enlarge.) On Tuesday, the International Space Exploration Coordination Group (ISECG), a group of 12 national space agencies that includes NASA, ESA, and Roscosmos, released a revised version of its Global Exploration Roadmap. The document is intended to outline a general strategy for human and robotic exploration over the next few decades, with human missions to the surface of Mars as the long-term goal.

The original version of this document, published in September 2011, offered two scenarios: an “Asteroid Next” approach that sent humans first to near Earth asteroids, then to the Moon and Mars; and a “Moon Next” alternative that sent humans first back to the surface of the Moon, then to asteroids and Mars. The new version offers a single scenario closer to the “Asteroid Next” approach, with humans first going to a captured near Earth asteroid per NASA’s plans as part of its asteroid initiative, with human lunar missions included before crewed missions to Mars in the 2030s. Also included in the mix are “extended duration crew missions” in cislunar space, such as at a Lagrange point.

What is clear is that this roadmap is not intended to establish long-term or permanent presences on asteroids or the Moon, at least by government agencies. The near Earth asteroid aspect of the roadmap includes only two crewed missions to such bodies, at least one to the asteroid NASA seeks to redirect into lunar orbit. (Unlike the 2011 roadmap, the new edition makes no mention of any deep space human missions to near Earth asteroids.) Those crewed missions would come some time in the mid-2020s, after the EM-2 SLS/Orion test mission and perhaps even one of the extended duration crewed missions in cislunar space.

The roadmap sees human missions to the surface of the Moon some time in the late 2020s (about 60 years after Apollo 11), using lunar orbit or a Lagrange point as a staging post for such missions. But those human missons peter out in the early 2030s, and the report makes it clear there is no place n the strategy for an extended human presence on the Moon, at least led by national agencies. “[T]he mission scenario defines a lunar campaign with an ‘exit strategy’ consistent with moving forward with Mars mission readiness,” it states. “However, participating agencies recognize that the fundamental capabilities are available to suport additional missions in the event that lunar science or other exploration activities are identified.”

The expectation of the strategy is that commercial entities will take over activities in some of these areas as the agencies press on to Mars: the roadmap includes roles for commercial or government platforms in low Earth orbit to replace the International Space Station, and “potential commercial opportunities” in both cislunar space and the surface of the Moon (but not, oddly enough, near Earth asteroids, given that companies have recently expressed an interest in prospecting and mining such objects.) The roadmap treats these places less as interesting destinations in their own right than as places to gain experience for human missions to Mars.

By Jeff Foust on 2013 August 16 at 8:15 am ET The Washington Post published an interview yesterday with NASA administrator Charles Bolden, primarily discussing leadership issues Bolden has faced in his four years at the top of the agency. Towards the end, though, the Post asks Bolden about NASA’s plans to direct an asteroid, in particular asking if that plan meets the goal established by President Obama in his 2010 Kennedy Space Center speech of sending astronauts to an asteroid by 2025. The answer is worth excerpting in full:

Does the asteroid redirect mission, in which you send an astronaut to one that’s in lunar orbit, fulfill President Obama’s goal of going to an asteroid in 2025?

My answer is going to be flaky. The first segment we’ve got to do. We’ve got to identify and characterize many more asteroids than we have done so far. That’s essential for the protection of the planet. That’s critical.

The second segment, which is the redirect mission—it’s a robotic mission, it doesn’t involve humans at all—that’s really necessary for us to develop the technologies that we need to advance exploration. Is it absolutely necessary before you send humans to Mars to do that? No, but it sure would be nice to have all that risk brought down because you’ve done it with the asteroid redirect mission. If that’s successful and then we can get humans to an asteroid in lunar orbit, that more than fulfills my understanding of the president’s direction.

And this is subtle. I have this discussion with my science friends all the time and those who are purist. The president said by 2025 we should send humans to an asteroid. What he meant was, you should send humans to somewhere between Mars and Saturn, because that’s where the dominant asteroids in the asteroid belt are. But no, he didn’t say that. He said: humans to an asteroid.

There are a lot of different ways to do that. There are probably thousands of ways to do it. I think we have come up with the most practical way, given our budgetary constraints today. We’re bringing the asteroid to us.

And so whether I put an astronaut on an asteroid that’s in lunar orbit or put an astronaut on an asteroid that’s still in orbit around the sun between Mars and Jupiter, I don’t care. What’s important is: Have them there.

Bolden’s claim that President Obama meant “you should send humans to somewhere between Mars and Saturn, because that’s where the dominant asteroids in the asteroid belt are” is sure to raise more than a few eyebrows. It’s unlikely the president meant, or many interpreted him as meaning, that humans should go to the main belt (between Mars and Jupiter, not Saturn), a mission that would rival a Mars mission in its length and level of risk. Instead, the assumption was that NASA would send humans to a near Earth asteroid, a mission that could be accomplished on round trips of a year or less, depending on the specific mission.

In any case, Bolden argues that sending humans to an asteroid redirected into lunar orbit satisfies the goal in the president’s 2010 speech of humans to an asteroid, and helps buy down the risk for future humans Mars missions given current budget constraints. But even that is not universally accepted (perhaps a hint to the discussions he says he has “with my science friends… and those who are purist.”) For example, earlier this year, speaking at a meeting of the National Academies committee on human spaceflight, Steve Squyres noted that the president’s 2010 speech called for sending humans “beyond the Moon” to an asteroid in deep space, something that a mission to a very small asteroid redirected into lunar orbit would not appear to strictly satisfy.

By Jeff Foust on 2013 August 15 at 11:33 pm ET A flat funding profile for the indefinite future increases the risk that NASA’s Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV) spacecraft will fall behind schedule, and will also delay the development of follow-on systems needed for missions to the surfaces of other worlds, according to a report released Thursday by NASA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG).

“The incremental development approach NASA has adopted for the MPCV puts the Program at risk for increased cost and schedule delays,” concluded the OIG report. That incremental approach, it stated, is necessary since Orion does not have the traditional bell-shaped funding profile, but is instead projected to receive a constant $1 billion per year through 2018, according to the administration’s fiscal year 2014 budget proposal.

Under this incremental approach, the report states, managers “allocate available funding to the most critical systems needed to meet the next development milestone.” The OIG concludes warns that this could lead to schedule and cost problems down the road, including some tests that have already been delayed, such as a test of Orion’s abort system that has been delayed four years to 2018. The program also have to overcome some technical problems, including the capsule being above its target weight and cracks in its heat shield.

Even if Orion overcomes those problems, the OIG report warns that there may be little for the spacecraft to do beyond orbital missions until the late 2020s because budgets don’t allow the development of additional exploration hardware. ” Under the current budget environment, it appears that obtaining significant funding to begin development of any such additional exploration hardware will be difficult and such development is unlikely to begin until sometime into the 2020s,” the report concludes. “Given the amount of time and money necessary to develop this hardware, it is unlikely that NASA would be able to conduct surface exploration missions until the late 2020’s at the earliest.”

By Jeff Foust on 2013 August 14 at 9:07 am ET Just before Congress adjourned earlier this month for summer recess, two members of Congress introduced a bill that they argue will help streamline commercial spaceflight regulations. Congressmen Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) and Bill Posey (R-FL) introduced HR 3038, the Suborbital and Orbital Advancement and Regulatory Streamlining (SOARS) Act.

“I have seen firsthand how the talented people of East Kern County have grown this industry through technological advancement, and this legislation will help ensure they are not hindered in creating jobs here locally,” said McCarthy, the House Majority Whip whose district includes the Mojave Air and Space Port, in a press release announcing the bill. “Our bill is a big step in streamlining FAA regulations and establishes demonstration projects for space companies supporting launch activities to safely move forward,” added Posey in the same statement.

One element of the bill would allow an experimental permit for a suborbital vehicle to remain valid even after a launch license is issued for that particular vehicle design. Under current law, the permit becomes invalid when a license for the vehicle is issued. That prevents one copy of a vehicle to perform test flights under a permit if another vehicle of the same design is operating under a license.

Another element of the bill would require the FAA to create a “demonstration project” for using experimental aircraft for “the direct and indirect support of commercial space launch and reentry activities.” The FAA would bring into this project no fewer than eight companies, with one at each currently licensed commercial spaceport. (The bill would allow the FAA to redistribute that allocation of companies if there are spaceports looking for more companies and others with none, a likely event as some spaceports are focused on vertical launch.) The demonstration period would run for two years, and the FAA would have the ability to extend it after that for two years at a time.

What would these companies would do with experimental aircraft? The “indirect support” is defined as training, testing, and other preparations for pilots, spaceflight participants, and payloads. The “direct support” element, though, could allow aircraft to support air launches of commercial vehicles—like Virgin Galactic’s WhiteKnightTwo, the air-launch platform for SpaceShipTwo—under an experimental aircraft designation, rather than as a certified aircraft.

By Jeff Foust on 2013 August 10 at 9:26 am ET In the last couple of months, NASA has appeared to put a greater emphasis on the role its overall asteroid initiative, including the Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM), could play in planetary defense. However, in a meeting last week, NASA administrator Charles Bolden appears to play down the role the mission could play in planetary defense or science.

“I don’t like saying we’re going to save the planet, for example,” Bolden said in a meeting of the NASA Advisory Council (NAC) on July 31 in Washington. “At some point, that may be done, but that’s not—we’re not in a position that we should be saying, ‘Fund the asteroid initiative and we’re going to save the planet.'”

He also deemphasized the role of science in the proposed mission to redirect an asteroid into a “distant retrograde” lunar orbit to then be visited by a crewed Orion spacecraft. “We should not be saying that this is going to benefit science. It is not a science mission,” he said. He said that the mission would accomplish some science, including by astronauts bringing back samples of the asteroid, “but it should not be characterized, or we should not try to characterize it, as a major science initiative.” What the asteroid mission will do for planetary science, he concluded, was “peanuts.”

Instead, the asteroid initiative was designed to advance long-term human space exploration in a time when the budget doesn’t exist for human missions to the Moon. “When I weigh the cost benefit of going back to the lunar surface in a limited budget environment, and going to Mars, I would rather take what little money I have upfront and advance the technologies we’re going to need” to do Mars missions, he said. He cited as one example the development of solar electric propulsion, something he said isn’t needed for a human return to the Moon but is useful for Mars and other deep space missions.

That downplaying of the role of the ARM for science or planetary defense aligns with the findings from last month’s meeting of NASA’s Small Bodies Assessment Group (SBAG) in Washington. Referring to the ARM as the ARRM (Asteroid Redirect and Return Mission), the SBAG found it wanting both in science and planetary defense.

“ARRM has been defined as not being a science mission, nor is it a cost effective way to address science goals achievable through sample return,” the SBAG found. “Robotic sample return missions can return higher science value samples by selecting from a larger population of asteroids, and can be accomplished at significantly less cost… Support of ARRM with planetary science resources is not appropriate.”

The SBAG also noted that since the mission would focus on redirecting an object no more than 10 meters across (although there is some discussion of visiting a larger asteroid and plucking a smaller boulder off it), “ARRM has limited relevance to planetary defense.” In addition, the group cited concerns about technical, cost and schedule risks, as well as poorly defined mission objectives.

With regards to schedule, one interesting item came up during the NAC meeting. Previously, NASA had talked about redirecting an asteroid to provide a destination for the first crewed SLS/Orion mission, designated Exploration Mission 2 (EM-2), planned for launch in 2021. One challenge has been, though, finding a target that, even in the most optimistic scenarios for the development of the robotic ARM spacecraft, could be put into te designed distant retrograde orbit by 2021. In a briefing about the initiative at the NAC meeting, NASA’s Michele Gates said “our current concepts are looking at either EM-3 or EM-4″ for the Orion mission to the asteroid. That would likely push out the mission into the mid-2020s, given the expected cadence of at least two years between SLS/Orion flights.

By Jeff Foust on 2013 August 8 at 6:34 am ET Monday night marked the first anniversary of the successful landing of NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover. While NASA celebrated the milestone with a recap of the mission’s accomplishments to date and plans for the future, one member of Congress used the anniversary to call attention to the funding squeeze the agency’s planetary science program is facing.

“[T]the amazing pictures and the public pronouncements hide an ugly truth — that the nation’s planetary science program has been under sustained attack from White House budget cutters and remains in jeopardy,” writes Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA) in an op-ed in the Los Angeles Daily News published on its web site late yesterday. He notes these cuts are not solely due to sequestration or other budget-cutting efforts but instead “deficit hawks in the Office of Management and Budget have targeted specific parts of the NASA portfolio for disproportionate cuts, and none more so than arguably the most successful of all NASA’s recent achievements — planetary science.”

Schiff discusses recent efforts, including that by the House Appropriations Committee (Schiff is on the Commerce, Justice, and Science subcommittee, which funds NASA) to restore at least in part funding for planetary science. The House’s CJS appropriations bill would give planetary science just over $1.3 billion in 2014, with the Senate’s version offering a nearly identical amount. Both are $100 million higher than the administration’s request, but still well below the $1.5 billion planetary received in 2012. (Not mentioned in Schiff’s op-ed is that it’s still not clear how much planetary science has to spend in 2013: as of last week, there was still no approved operating plan for the agency with just two months left in the fiscal year.)

Schiff also addresses question on why planetary science should get this or any amount of funding in the current fiscal environment. “Plainly, the bureaucrats at OMB think the search for life on other planets to be an expensive, quixotic and dispensable activity,” he writes. “These missions preserve America’s edge in a host of technologies that are key to maintaining our global leadership. Profoundly important research and development and all the economic benefits it brings will be forsaken if we abandon the field.”

|

|