By Jeff Foust on 2008 July 19 at 7:14 am ET One of the first panels Thursday at the Space Frontier Foundation’s NewSpace 2008 conference was titled “VSE: The Beginning of the End or the End of the Beginning?” The VSE, of course, referred to the Vision for Space Exploration, the national space exploration policy introduced in January 2004. Except that, earlier this year, the policy was quietly renamed the US Space Exploration Policy (although references to the former name are still on the NASA exploration web site). Or does the policy need a new name altogether?

“If we’re going to talk about sustainability, in my opinion we need to use a different vocabulary,” said Paul Carliner, a former Senate staffer. “I think we need to stop calling it the Vision for Space Exploration. A ‘vision’ is a word that connotes something of a plan for the future. This is not a plan for the future. This is a program that is ongoing, is current.” He noted the policy’s endorsement by Congress in the NASA Authorization Act of 2005 and the spending of billions of dollars on Ares, Orion, and other exploration-related programs. “That’s not a vision, that’s a program.”

What, then, should the exploration effort be called? “The current name is Constellation,” he said, referring to the term usually reserved for the transportation components of the plan. “We all need to start using that name of the program when we discuss what we’re talking about.” Carliner said that in the 1960s, the push to send a man to the Moon was not the “Vision to Send a Man to the Moon” but became known by names like Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo, “names that to this day still have an iconographic status with the American public and the world.” Calling the current effort the Vision could be damaging to its long-term prospects, he said. “If we refer to it as that, nothing more than a plan for the future, then it becomes very easy not to sustain it.”

Another panelist, former White House staffer Brett Alexander, said that Constellation may not be the right name. “Calling it Constellation does kind of leave out that space science part,” he said. He noted that the original policy had the title “Renewed Spirit of Discovery”, a term that never gained much currency with NASA or the public. “The ‘Vision for Space Exploration’ was a name made up by NASA and [then-administrator] Sean O’Keefe at the time. It was apt, but it has outlived its usefulness.”

By Jeff Foust on 2008 July 18 at 6:12 am ET At the Space Frontier Foundation’s NewSpace 2008 conference in Crystal City, Virginia on Thursday, a group of over a dozen organizations announced the formation of a National Coalition for Cheap and reliable Access To Space (CATS). The purpose of the coalition is to “put cheap access to space back on the national agenda,” in the words of coalition coordinator Charles Miller. The coalition will develop a “declaration” for CATS over the next four to six weeks, including during a meeting at the DC-X reunion conference next month in New Mexico. That will be followed by a National Summit on CATS that will be held on the campus of Ohio State University on October 7-8 that will delve into how to achieve CATS. Why there? “Ohio is a battleground state” in the upcoming presidential election, Miller said; the Ohio Aerospace Institute is one of the member organizations in the coalition as well. The coalition will ask CEOs of major corporations and non-profits to sign the declaration, which will then be presented to the next president after the November election.

Although the location of the summit is based in part on the state’s role in the election, Miller said that the coalition does not have specific plans to engage with the campaigns prior to the election. “We don’t think that the campaigns will be able to hear this” because of all of the other issues during the campaign. Miller said that they are building inroads into both the McCain and Obama campaigns so that they’re prepared to discuss this with the winning campaign after the election, but not earlier.

By Jeff Foust on 2008 July 18 at 5:49 am ET Today’s Houston Chronicle report that Houston-area congressman John Culberson wants to introduce “revolutionary change” to NASA by completely restructuring the 50-year-old agency. Culberson, a bona fide space geek (in the best sense of the term), wants to model NASA on the National Science Foundation so it can “be driven by the scientists and the engineers” and “be free of politics as much as possible”.

How exactly Culberson proposes to do that isn’t clear: he hasn’t drafted any legislation on this, he told the Chronicle (which means that there’s no chance of anything happening on it this year), and didn’t go into details about how NASA would be transformed. While NASA and NSF are often closely linked as “science” agencies (although NASA is more than just science), the two organizations are very different, and it would seem at first glance very difficult to convert NASA into an NSF-like organization. For example: NASA has tremendous amounts of infrastructure, from field centers to space hardware; NSF, by comparison, has very little. Would NASA retain that infrastructure after that transition? If yes, how would it be run differently? If not, who (if anyone) would take if over, and how would they operate it for NASA?

The Chronicle notes that Culberson also made comments during an online town hall meeting earlier in the week that, on their surface, appeared to be disparaging towards NASA. “We’ve spent a fortune on NASA, and we don’t have a whole lot to show for it,” Culberson was quoted as saying, adding that “NASA wastes a vast amount of money.” Some might argue that those statements aren’t that controversial, but in the Houston area, they did generate a backlash from Culberson’s Democratic opponent and Rep. Nick Lampson (D-TX), whose district includes JSC. “It’s times like these when I’m relieved – and I know my constituents are relieved – that I’m the representative of JSC,” Lampson told the paper.

By Jeff Foust on 2008 July 18 at 5:21 am ET As I noted here earlier this week, there is growing interest in alternative energy efforts that could end up competing with space exploration for federal funding—even as alternative energy advocates use the Apollo program as a model for their efforts. Now there are a couple more examples which demonstrate this trend.

An editorial in Wednesday’s Houston Chronicle made the case for an “Apollo-scale” program for alternative energy (in addition to increased offshore drilling):

If President Bush and Democratic leaders in Congress wished to show responsible leadership worthy of the public’s growing concern about high energy costs, they would together craft legislation that would encourage domestic energy production and begin a national research program – on a scale of NASA’s successful race to the moon – to develop clean energy from renewable sources such as wind and sunlight; superefficient batteries in which to store it; and alternative fuels such as hydrogen or some source not yet envisioned.

Then, yesterday, former vice president Al Gore made a similar call for alternative energy development:

Just as John F. Kennedy set his sights on the moon, Al Gore is challenging the nation to produce every kilowatt of electricity through wind, sun and other Earth-friendly energy sources within 10 years, an audacious goal he hopes the next president will embrace.

Such large-scale programs, if implemented, would be expensive, just as Apollo over 40 years ago. Where would that money come from, particularly if the presidential candidates are serious about reducing budget deficits? Lots of other programs would probably be under pressure, and it’s hard to see how NASA would be exempt.

By Jeff Foust on 2008 July 17 at 6:36 am ET Last night several organizations co-hosted a “Teachers in Space” roundtable at George Washington University. The idea behind Teachers in Space, unlike NASA’s Teacher in Space program in the 1980s and the current group of educator astronauts, is to fly current teachers on suborbital spaceflights using any number of commercial vehicles currently under development, then get the teachers back in the classroom so they can share their experience—and, presumably, enthusiasm—with their students. Most of the panel discussion focused on the benefits of the program as well as the history of NASA’s past teacher-in-space efforts.

The roundtable came after three days of Congressional staff briefings by several people affiliated with Teachers in Space. Project manager Ed Wright said that they held several dozen briefings and were pleased with the results; he cited one hour-long briefing earlier in the day with a Congressional fellow who was particularly excited about the concept.

Right now, though, Teachers in Space isn’t seeking any specific legislation or federal funding. Wright said that they did get some commitments of support, up to offers to introduce legislation on the issue if needed, and also got feedback on how to win federal funding to help support this project. (Teachers in Space has several flights donated to it by several vehicle providers, and has also arranged a purchase of flights from XCOR Aerospace.) One earlier proposal called for funding flights of 500 teachers a year: one from each Congressional district plus several dozen others.

Charles Miller, president of Space Policy Consulting, said that it might still be too soon to pursue specific initiatives like that. “If you started a Teachers in Space program right now, 500 teachers per year, it would change how the Hill perceives risk,” he said. “They would probably try to put more burdensome regulations on the emerging industry, which is not ready for it, because you’re protecting the teachers.” He expected that in the next few years, once suborbital vehicles begin flying, and flying safely, that teachers, perhaps supported by funding from Congress, will soon follow. “It may not be the right idea right now, but within the next five years, they [Congress] could see it being the right idea,” Miller said.

By Jeff Foust on 2008 July 15 at 7:14 am ET That’s the topic of an article in this week’s issue of The Space Review that I wrote about the potential risk to civil space programs posed by growing concerns about energy and desires for crash programs to develop alternative energy sources. Both major presidential candidates have appropriated arguably the biggest accomplishment of the Space Age to date—the Apollo lunar landings—as a way to describe the level of commitment (and size of funding) needed to gain “strategic independence” in energy (in John McCain’s words) or otherwise develop alternative energies.

That level of effort will require a lot of money: Barack Obama’s energy policy calls for $150 billion over 10 years for alternative energy research. Coupled with desires to reduce deficit spending, as well as growing pressure on the budget from mandatory spending, will space feel the squeeze in the next administration? As I conclude the article:

…but new energy policies will add to the existing fiscal pressures on NASA and space exploration in the next administration and beyond. That makes it all the more imperative for NASA and its supporters to craft approaches that are cost effective and also exciting and inspiring, to help win public support and thus funding. Otherwise, the Vision for Space Exploration and efforts like it might run out of gas.

In a related article, Greg Anderson examines what it takes to build long-term support for government initiatives of any kind, from Social Security to the Cold War, and how that can be used to build support in future administrations for space exploration. His conclusion: “Space expansion, therefore, must be presented to voters as being good for society as a whole. If the enemy in the Cold War was Communism, the alternatives to expanding the human economy beyond Earth are poverty, stagnation, and smaller, perhaps shorter lives for coming generations.”

By Jeff Foust on 2008 July 11 at 7:31 am ET Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords (D-AZ) has probably gotten more attention than the typical freshman representative, in large part because of who she’s married to: NASA astronaut Mark Kelly. In an interview with Politico, she discusses that as well as a few other space-related issues:

- “NASA is an extension of how the United States has been a leader historically in science and technology,” she says. “But unfortunately, just like in many other areas, NASA is falling behind.”

- Talking about human exploration of Mars, she’s obviously not enthused about having her husband go on a one-way trip to Mars. As for others, “The whole purpose of sending humans into space is so they can come back and tell us what they can see.”

- Asked if she’s interested in flying in space herself, she said she was, and spoke favorably about ventures like Virgin Galactic. “I couldn’t afford that,” she said, citing its $200,000 price tag. “But I think someday in our lifetime an experience in space for the Average Joe will be more cost effective.”

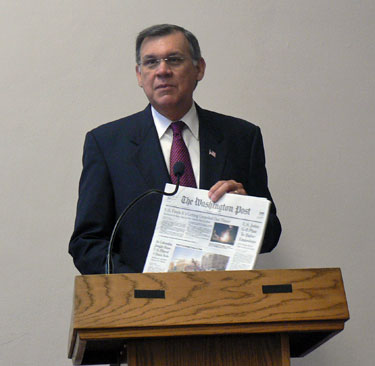

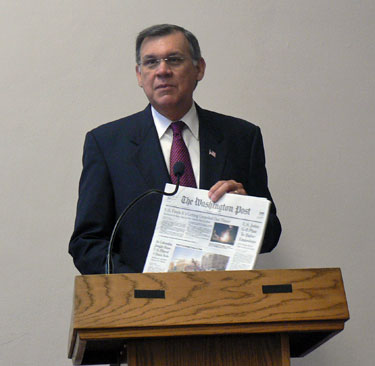

By Jeff Foust on 2008 July 10 at 7:54 am ET So why was Sen. Mel Martinez brandishing a copy of the Washington Post Wednesday morning?

He was referring to a front-page article about the rise of other countries in space as he started his remarks at a Capitol Hill event organized by Women In Aerospace. “The United States needs to recommit to spaceflight, needs to recommit to a future of exploration where we have led the way,” he said. “What’s going in the next several years I consider to be not only a threat to our national security and sovereignty but also a real honest-to-goodness challenge.”

During his remarks, and a brief question-and-answer session that followed, he expressed his concerns about the gap between the retirement of the shuttle and the introduction of Constellation and the several thousand jobs predicted to be lost at the Kennedy Space Center. “As a nation, a five-year gap in spaceflight is just too long,” he said. “It isn’t right, is isn’t what America’s about. So I would love for us to somehow find a way to shrink that gap.” He didn’t specify how that gap should be shortened, but did say, “if we were to add a billion dollars to the NASA budget, we could substantially shorten the gap.” (He may want to check with Jeff Hanley about that.)

Asked if he felt the agency’s current direction, including human missions to the Moon and eventually Mars, was the right way forward, Martinez admitted that he did not personally find current work on the space station that exciting. “I don’t know what happens up there. I mean, I keep up with it, but I don’t know of anything I can relate to. I can’t get anybody excited about the thought of, ‘Man, I’m going to go up there and stay for six months and do whatever they do.’ That’s not quite it.” Therefore, he said, “visiting other places” like the Moon might be much more exciting to the public.

Martinez was also asked if he talked with John McCain or others in his campaign about his economic proposals, including a discretionary budget freeze that, coupled with the likelihood of a continuing resolution for part or even all of FY 2009, would seem to exacerbate the gap and the potential job losses on the Space Coast. “You know, I have not, and I need to do it; that’s a very good point,” Martinez said. He then pointed to a staffer in the back of the room. “You know, Michael, that’s something we should pursue.”

(Disclosures: 1) The Post article includes references to work performed by my employer, and a quote from the company president. 2) I am an officer in Women in Aerospace.)

By Jeff Foust on 2008 July 10 at 7:02 am ET An editorial in Florida Today calling for more money for NASA isn’t exactly novel. Fortunately, in another such editorial today the paper realizes it’s treading on familiar ground:

Which brings us to a point we’ve been making repeatedly on this page and need to make again:

If America wants to remain the world’s major spacefaring power, the next president has to recognize the economic, technological and scientific importance of NASA’s lunar program and support it with stable, long-term funding to get it off the ground.

Otherwise, it will stumble in fits and starts, falling further behind schedule while surging space powers such as China move ahead.

So they want the presidential candidates to speak out on this issue:

That’s why John McCain and Barack Obama should make it unmistakably clear during campaign stops in Florida, Texas and other NASA-dependent states that returning to the moon — and later going to Mars — are noble goals that will benefit the country the way project Apollo did a generation ago.

And the mission has their complete backing.

Some might consider such an approach—talking up NASA only in places where there is a significant agency presence—pandering for votes, rather than laying the foundation for a solid, rational space policy. Making such statements in Peoria, Paducah, or Poughkeepsie, on the other hand, is a different story.

The editorial does make one notable error:

For instance, House members last month voted an overwhelming 409-15 to increase the agency’s budget to $20.2 billion for fiscal year 2009 — $2 billion more than President Bush has requested.

The extra money would go for an additional shuttle flight to finish building the International Space Station and development of the Ares 1 rockets and manned Orion spacecraft that will carry astronauts to the moon from Kennedy Space Center.

The money probably won’t survive the Senate and Bush says he’ll veto the funds if they pass, but it’s an important signal to the next White House occupant the space program has broad, bipartisan support.

The $20.2 billion referred to above is an authorization, not an appropriation, and the Senate is likely to approve a similar figure. However, both the House and Senate are considering significantly smaller figures, about $17.8 billion, in their appropriations bills (subject to efforts like the “Mikulski Miracle” to add additional funding). It’s relatively easy to authorize spending large sums of money; actually appropriating the money, on the other hand, is much more difficult.

By Jeff Foust on 2008 July 10 at 6:43 am ET Is there anything that the House didn’t honor yesterday? The House took up no fewer than four resolutions recognizing people, agencies, organizations, and even years with space-related links:

- H.Res, 1315, commemorating the 50th anniversary of NASA;

- H.Res. 1313, celebrating the 25th anniversary of the shuttle flight of Sally Ride, the first American woman in space;

- H.Res. 1312, commemorating the 2th anniversary of the Space Foundation; and

- H.Con.Res. 375, honoring the International Year of Astronomy in 2009.

None of these, of course, are terribly controversial. The latter two passed on voice votes Tuesday, while the first two still require the formality of a roll call vote.

|

|